The Long Journey Home review – space-sim for the patient ones

Deep space exploration has recently become wildly popular in video games. How did Daedalic approach this theme in their new game, The Long Journey Home? What distinguishes it are diversity, creativity… and the fact that it’s hardcore. It really is.

The review is based on the PC version.

- Big, procedurally-generated world;

- Quite a lot of diverse races and diplomatic relations;

- Music fits the stellar journeys well;

- Many cool, fun tidbits and minor occurrences, including quests with multiple endings;

- Planets have varied biomes and atmospheric conditions, plus a day-night cycle;

- The influence of gravity on the ship is a brilliant concept…

- … which may drive less patient players into madness;

- Unintuitive flying mechanics;

- Irksome minigames and mundane shooting;

- Consequences of mistakes are out of proportion;

- The lowest difficulty level is something around VERY HARD;

- No reward for the effort, patience and understanding that you put in.

It hasn’t been that long since we were all in awe of the first announcements of No Man’s Sky. Then our optimism vanished behind the event horizon of disappointment, and we were crushed by the asteroid called Reality. Since then, I’ve been wandering around video game stores, looking for something to soothe the pain, and clutching to the slightest scrap of hope. I believed that one day a special space game would come and make me seal the airlocks of my flat, cut all communication with Earth, and venture off into the stars. Mass Effect Andromeda failed to deliver; I don’t even want to talk about the Hello Games case anymore; I’m looking towards Star Citizen with a certain amount of hope, however dampened by suspicion and reservations. Fortunately, the market today is expanding faster than the Universe, and is full of unassuming little gems that lack the notoriety of bigger titles. The Long Journey Home was supposed to be exactly this.

Isn’t this a nice name? Daedalic West had a simple idea – simple but appealing. You start by choosing four brave men and women who will plunge into the unknown – our choices may decide the success or failure of the great cosmic odyssey. Who would you rather have – a great pilot, scientist or engineer? Then you need to decide which ship and which Lander you want. Needless to say, everything’s described by a number of stats, all of which are of critical importance in different circumstances. There’s no perfect ship, and the Cosmos is full of hazards; would you rather have better hull, bigger fuel capacity, or an engine capable of performing more hyperspace jumps? Finally, after finishing the tutorial, during which – rest assured – you will watch your lander perish amidst the arid Martian landscape more than once, it’s time for your first jump. The board is green, the engines are hot, the ship enters hyper light speed and… bang.

The Big Bang Theory

You’re millions of light years away from home, alone and lost in the vast nothingness of space. Your ship is badly damaged, and one of your crewmates complains about his spleen. Cosmic journeys are no trifle – time to find a planet that could yield some resources critical for survival. It’s not an easy business, surviving, I can tell you that.

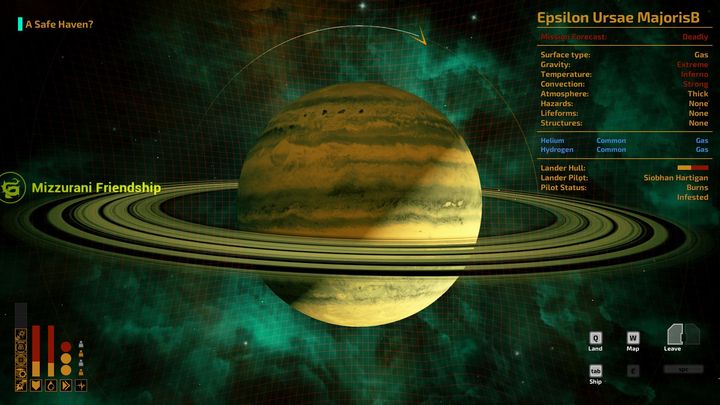

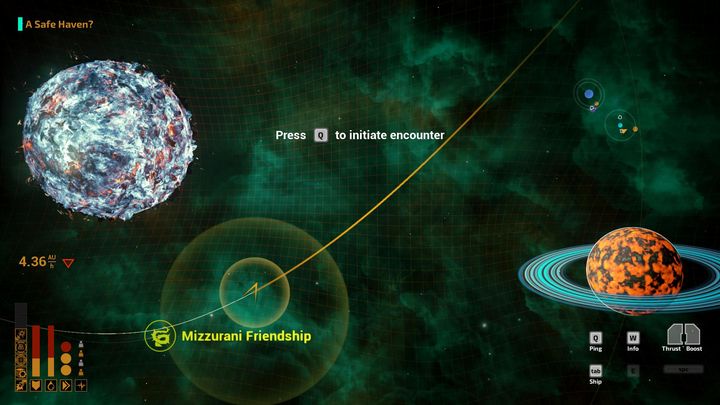

The Long Journey Home is an indie game, the ambitions of which begin somewhere in the area of FTL: Faster Than Light, and end in the No Man’s Sky vicinity. Sadly, the execution doesn’t rise up to the occasion. After choosing the crew and the ship, the journey into the stellar expanse begins and you’re sitting there, terrified, watching the indicators showing the condition of the hull and the astronauts, and the amount of fuel. The ultimate goal is going back to Earth – in order to be able to do that, you need to reinforce the ship and develop relationships with aliens. And so you’re roaming the alien galaxy, orbit planets, land on them to gather resources, engage in arguments with sentient fish that are able to harness the power of nuclear fission, and generally try to stay alive.

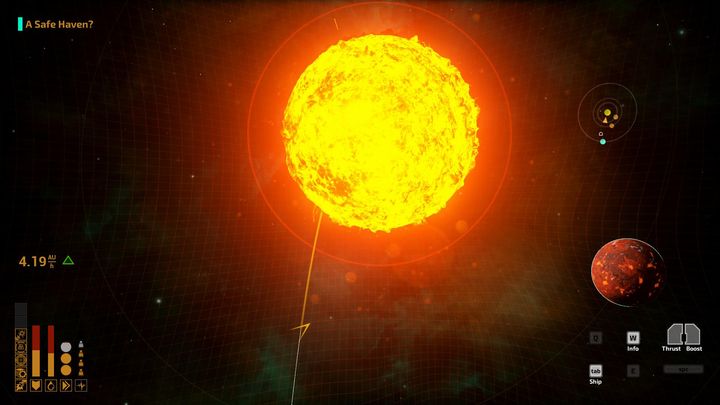

Don’t let the trailers deceive you: most of the time, your ship is just a tiny arrow moving along ellipses. You can manipulate the arrow by increasing thrust, hence altering the trajectory. The Long Journey Home shows everyone how interstellar travel is really done. You can’t just point your finger and say “There, helmsman, to the stars! Never mind the gravity well!”. When traveling, the force of gravity has to be considered; using engines alone to get from point A to B in a straight line would require massive amounts of fuel. Instead, gravity-assisted maneuvers are obligatory.

Newbie astronauts should keep in mind two things: one, orbits are ellipses, so it may take quite a bit circling around to finally get slingshot in the desired destination; you need some stellar patience. Never mind if you’re near a small planet, but the game features all known types of stars, including red super giants – doing a full orbit around these takes a lifetime, especially since you have to keep a certain distance because of the radiation.

Second: the controls of the ship I found rather annoying and uncomfortable. Get ready to mince curses when the small arrow – paying no heed to your frantic attempts to reverse its course – flies right into a star. The game doesn’t end if that happens – the autopilot takes control and helps to avoid the collision, but not without some serious damage being done to the ship. From the very beginning, it’s clear that you need two things to enjoy The Long Journey Home: patience and understanding.

Monty Python’s Cosmic Circus

And don’t get me wrong. I bet many people will be fascinated by this game; it will suffice for hours upon hours of gameplay, especially since the universe is generated randomly and the whole journey is… well, quite random. Although you’ll be doing the same quests with every playthrough, the world will always look different and you’ll never know what’s behind the next galactic corner.

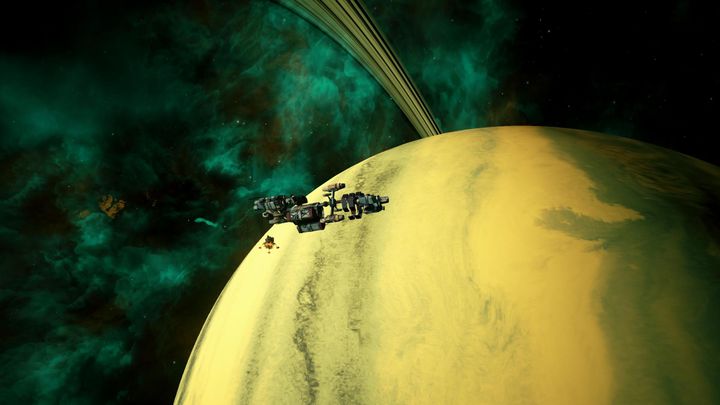

All kinds of planets can be encountered during the journey, such as huge, radiating suns, fields of asteroids, space stations and other spaceships traveling in an altogether more elegant manner. The player can interact with each of these objects, assuming that the weather and temperature allow a touchdown, enabling them to collect invaluable resources. You can enter asteroid belts (then the camera switches to a top-down view, and the ship indeed becomes a ship – as opposed to the minimalist arrow – lighting nearby space rocks with spotlights) in order to extract needed materials. The fuel required for hyper space jumps can be collected near stars, and a nice little close encounter of the third kind can be arranged, often ending with our crew being scanned for stellarly transmitted diseases and other kinds of cosmic parasites by the cautious aliens.

Even though the rougelike structure of the game gives it a serious overtone, the artistic convention is rather comical and exaggerated. The encountered aliens are mostly barmy jellyfish blessed by an incredibly forgiving evolution. And so the cosmic squid bounces around the galaxy like some dude in a ’92 Honda Civic, and they either are suspiciously friendly, or – quite often! – confiscate one item or another, because a galactic Geneva convention prohibits the use of AAA batteries. Really, the galactic community acts like a bunch of spoiled kids who got their hands on Gold Codes.

There’s a myriad of races here – the galaxy of The Long Journey Home doesn’t suffer from a Mass-Effect-Andromeda syndrome, and is populated by all kinds of civilizations. Each of them has a different appearance, attitude, and usually has a bee in their bonnet about artifacts concealed by parsecs of cosmic vacuum. You can see the developers made a point of making their universe interesting – and came out on top. You can get lost and you can find trouble. Things can take unexpected turns; I once encountered a race that was really welcoming (though I couldn’t shake off the impression that they were greeting me like an owner greets his half-intelligent dog), but then I gave a ride to a stellar hitchhiker – for which I was severely rebuked by the same race, and also suffered some humiliating sanctions, losing many precious items.

The races you bump into are not always friendly towards one another, and helping one may prompt the animosity of the other. On another occasion, I was forced to mount a transmitter on my ship in order to deter some other species – who immediately declared me wanted dead or alive. Yet another time, I met a race that decided to befriend me right off the bat and look for a new homeworld alongside my ship. They followed my every step. After a while, my fuel reserves were dwindling and I had to risk landing on a planet despite poor weather. It wasn’t easy but I pulled it off and managed to get back to the ship, where I got the message that my newly acquired friends had attempted to land right after me and… crashed. There’s a slew of instances like this one and the game constantly surprises us. So, first you’re exploring various planets (which even have their own day/night cycle), and then you’re trying to convince a talking sponge that you’re really a fun bunch of guys and gals. The architects of this cosmos prepared numerous diversions to our experience. You have to survive first, though.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

And finally, here we are, witnessing the game’s greatest disadvantage. The learning curve is as steep as it gets, which makes the game far from enjoyable during its initial stages. Everything, virtually every element of the game’s mechanics is not only hard to master – it’s hard to be even remotely assimilated. There are so many statistics describing our little flying circus that by the time you manage to elevate one of them to some reasonable level, five other problems will get you.

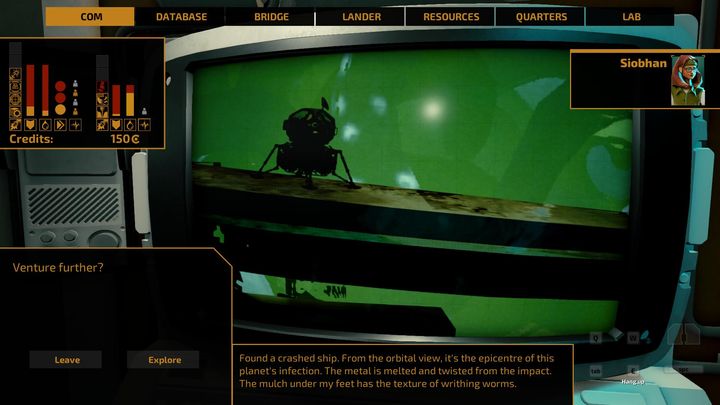

A typical game of The Long Journey Home is this: you casually approach a planet, where you hope to extract some fuel and ore to repair the hull. You confuse the trajectory three times and ram head-on into the planet. Finally you manage to catch the orbit and send the lander, which – despite fantastic weather conditions – slams into the ground full-throttle. The pilot shattered some bones, but says he’ll manage, so you take what you can and go back only to spend the ore you just brought to repair the lander you just broke. Every cloud has a silver lining though – you remember that there should be a repair toolbox squirreled away somewhere, so you should be able to replace some damaged ship modules. That’s not over, though.

A while later, an alien ship scans our little vessel, and figures that the toolbox is a grave threat to the delicate balance of power in the known universe. You can decline to give it to them, which will compel them to swap diplomats for commandos and their pleas for laser-guided missiles. You don’t want that. Let’s assume, however unlikely that is, that you survive that encounter and keep flying on. You get to another planet and crash the lander once again. The pilot catapults, but he now has four major injuries so god forbid he sneezes or coughs, or you’ll have no pilot soon enough (all characters are able to suffer five incidents). We’re going to the nearest space station to get a new lander, otherwise there’s no way of getting the resources needed to get back home. Then the ship runs out of fuel. Then out of oxygen. And then you run out of crewmembers.

2017: A Tragic Odyssey

It’s all part of the genre. Yeah, I hear you – roguelikes are supposed to kill us, and we are supposed to return richer with experience and keep going farther and farther. Yes, it’s all here – flying can be learned, quests can be repeated, and with a (significant) dose of luck, we can feel like astronauts on a crazy expedition. That said, when playing the old, text-based classic ADOM, after a defeat I would always return burning hot with excitement and ready to try again; when playing The Long Journey Home, first I felt irritation, then disappointment, and then, finally, the joy of space exploration.

The reason for that is not just the high difficulty level by itself, but a much more grave offence: the controls in this game are a real nuisance. Sure, you can tell yourself that it’s a simulation, that it’s space stuff, that it’s NASA, whatever – flying and planning in this game are bad and unpleasant, be it early or late in the game, and the player gets virtually no satisfaction from gradually mastering the interface. While the simulated gravity can be decent at times – because using a gravity catapult to flawlessly shoot ourselves from a low red dwarf orbit into a rocky planet is just that satisfying in itself (still, if you are able to fly without hitting any stars you have my deepest respect) – the planetary landings are a test, designed by mad psychologists, specifically to evaluate the limits of our patience.

The landing module moves as if, other than wind and gravity, it was controlled by a drunk freshman student. Even when the planetary conditions are favorable. Often we are forced to enter the atmosphere at such a high velocity (despite our attempts to reduce it) that we simply cannot slow down on time to avoid a crash. And yes, there is a way to remedy this, one that I’ve learned for the price of numerous breakdowns and smashed coffee mugs, but I’m afraid that most gamers will simple hit ALT+F4 and uninstall the game before they can learn the trick. Even if you finally do learn how to keep the lander airborne, you’ll notice that its controls are rough, unintuitive, and irritating. Frankly speaking, this space simply lacks fun.

This problem concerns virtually every single one of the minigames in The Long Journey Home. When we fly among the asteroids, our ship moves like... a moose on the surface of a frozen lake?! The arcade combat is neither spectacular nor does it motivate us to hone our skills and dexterity, and landing on an orbit around a small planet is like trying to drive through the eye of a needle. Let me say this again: all these maneuvers can be learned and mastered – and probably some of you will be able to do it. It’s just that the price for learning them will be too high, too galactic for most of the players, and certainly not worth the satisfaction.

Frankly, I find it sad, because although we like to feel special and better than fellow humans, we have to remember that forcing such attitude on the gamers is not the best thing you can do on a money-ruled market. In the case of this work from Daedalic, you could easily think that the developers were against many people exploring their space. Truly, few will be able to do it (and appreciate this game). And by this I do not mean the most talented hardcore gamers. People who get to fly will be the people with the patience and understanding of an angel. The rest of pilot candidates will probably serve as Martian dust.

The Long Journey Home was supposed to be a beautiful, memorable space trip, on which we would take the hopes and promises that were unfulfilled by previous titles. This, however, did not happen – the game would rather punish us than entertain, and I’m afraid that you’ll run out of oxygen before you can appreciate the complexity and beauty of this title.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I’ve spent more than a dozen hours in the cold space of The Long Journey Home, shared between crashing into ice planets and crashing into burning stars. I’ve burned, broken, suffocated, and blown up to bits several pilots. In the short breaks between dying I’ve completed some quests, helped some fish in need, and gathered resources.

Matthias Pawlikowski

The editor-in-chief of GRYOnline.pl, associated with the site since the end of 2016. Initially, he worked in the guides department, and later he managed it, eventually becoming the editor-in-chief of Gamepressure, an English-language project aimed at the West, before finally taking on his current role. In the past, a reviewer and literary critic, he published works on literature, culture, and even theater in many humanities journals and portals, including the monthly Znak or Popmoderna. He studied literary criticism and literature at the Jagiellonian University. Likes old games, city-builders and RPGs, including Japanese ones. Spends a huge amount of money on computer parts. Apart from work and games, he trains tennis and occasionally volunteers for the Peace Patrol of the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity.

more

The Long Journey Home review – space-sim for the patient ones

game review

Deep space exploration has recently become wildly popular in video games. How did Daedalic approach this theme in their new game, The Long Journey Home? What distinguishes it are diversity, creativity… and the fact that it’s hardcore. It really is.

Princess Peach: Showtime! Review: Setting the Stage

game review

Peach finally has her own game after years in Mario’s shadow. With new transformations that give her a slew of abilities, is that enough to make her game a hit?

Alone in the Dark Review - It Ain't Easy Making a Classic Come Back

game review

A famous franchise makes a comeback with its modernized reboot, but can it live up to the legacy?