Bigger doesn’t mean better - was the original Assassin’s Creed the best one in the franchise?

Although lately criticized for its modest contents and repetitiveness, the first Assassin’s Creed possesses some undisputable redeeming qualities that were lost in subsequent installments – its distinctive character and tremendously immersive gameplay.

I suppose many of you, after having read the title above, look at my words with a newly-found suspicion of my mental health. I mean, by what wicked logic is the series’ repetitive, crude, and lacking in content forefather better than Assassin’s Creed II, a nearly perfect game that improved on virtually every aspect and covered up all of the most irritating shortcomings of its predecessor. How can bleak Altair and the desolate deserts of Levant during the Crusades make a better combination than charismatic Ezio and the vivant Italian Renaissance. No, never. I wouldn’t even dare to try convince you otherwise – AC II proved to be both groundbreaking AND breathtaking, quickly rendering the first game in the series pale in comparison. The thing is, this article is neither about the perfected gameplay mechanics and open-world environments nor about the mental traits of the protagonists – that’s precisely, and with no doubt, where Assassin’s Creed II and later installments take the cake. Instead, I’d like to focus on a more subtle matter, namely the relation between the game’s futuristic premise – the Animus being used in the present to delve into the past – and various gameplay mechanisms. In general, I’d like to discuss with you what made the original Assassin’s Creed so distinctive and immersive in the first place; all the more so, seeing those characteristics waning, substituted year after year with uninspired sandbox “features” (and equally uninspired plotlines).

An assassin lives and dies by the creed

Let us go back in time, to the year 2007, when AC I was officially announced. With the release of the initial trailer, we have learned that Ubisoft was developing an action game set in the Holy Land during the Third Crusade and that we’ll be stepping into the shoes of an assassin, eliminating his targets among European crusader knights and Saracen defenders alike. From the very beginning, though, we knew that there was something more behind that historical setting – the mysterious noises and blurs visible on the trailer suggested as much. Indeed. The actual setting of the franchise’s plot is – or should I say “was”, having seen its current direction that stubbornly marginalizes this aspect – the present, and the past events are (were) nothing more than means to allow present characters achieve various objectives in their epoch. As it turned out, gameplay-wise the situation looked very different, but let’s leave the gameplay out of this, for now at least. The tool that enables us to form a connection between that which is and that which was is the Animus – a machine able to read human genetic memory and visualize the events from the life of subject’s ancestors in the form of a realistic simulation.

Seeing as this article focuses on the first Assassin’s Creed, let me refresh your memory with this plot digest. The year is 2012. As Desmond Miles, a simple bartender, we awake to the fact of having been abducted by the Abstergo Corporation to have the genetic memory of our ancestors mined using a virtual reality interface called the Animus. In time we learn that the corporation is searching for an artifact known as the Apple of Eden, and the plot revolves around the unending conflict between the Assassins (with Desmond turning out to be their descendant) and the Templars (represented by Abstergo).

The whole Assassin’s Creed franchise is based upon this brilliant concept, but it is the first installment that draws on it the heaviest. Virtually every element of the game served the Animus and the whole idea of synchronization: forming and maintaining a connection between the human sitting in front of the screen, the character using the Animus, and his ancestor whose memories are being visualized. The Animus user must try to “reenact” the role of his forefather to sustain the connection and avoid getting kicked out from his memories.

And so we arrive at the unique element that like no other sets the first chapter apart from the rest of the cycle – the synchronization meter. While it appeared to be a typical health bar – we lose health (synchronization) when injured in battle or falling from heights, and “die” (desynchronize and get expelled from the simulation) when the bar gets empty, which forces us to reload last checkpoint. However, there is more to it; not only we lose synchronization for having killed innocent people, we can permanently increase our max level of synchronization by engaging and completing as many side activities as we can – complete “investigation” sections before all the major, plot-driven assassinations, collect flags, eliminate Templar knights, etc. We can gain up to an additional 1/3 of the synchronization meter this way (7 bars out of 20). In itself it is quite a common character progression system; in Assassin’s Creed, however, it goes deeper than that. Every such action is justified by the plot – by completing these activities you and Desmond are acting exactly as the “original” Altair would have acted, thus increasing your synchronization and allowing you to commit more mistakes before the connection with the ancestor’s DNA gets severed.

Regaining lost synchronization is also an interesting matter. The meter recovers automatically in time, but the rate at which it recovers depends on our gameplay style – it is goes faster if we act as a true assassin would, which means we avoid drawing unnecessary attention, prefer the hidden blade over hacking our enemies with a sword, etc.

That’s the second distinctive characteristic of AC I: the eponymous Creed. Looking back now, it may seem comical but, beginning with the second installment, Ubisoft began to omit this element. The element which – considering the franchise’s title – should be the foundation of all the subsequent entries. What is left is the corny catchphrase “Nothing is true, everything is permitted”, which can be interpreted freely and according to one’s imagination. It was the breaking of the three tenets that caused Altair’s punishment in the first place. The three tenets that are getting hard to find in the recent Assassin’s Creed games:

- “Stay your blade from the flesh of an innocent.”

- “Hide in plain sight.”

- “Never compromise the Brotherhood.”

The reason for putting the tenets aside is rather mundane, but we’ll get back to that later; let’s finish the topic of correlations between the Animus and gameplay mechanics in AC I. The mission order and world exploration were dictated by the idea of connecting to genetic memory through a machine. In theory, Abstergo should have been able to go straight to the relevant memory, mine it, and terminate their “cooperation” with Desmond at that point. In practice, Desmond’s subconsciousness blocked any attempts to connect directly to the DNA sequence they wanted. That’s the reason why the Templars were forced to pave through all the adjacent memory sections – and also how we got a series of subsequent missions (assassinations) to complete. It also constitutes the explanation why the subsequent districts in the three towns in which the game takes place were unlocked gradually.

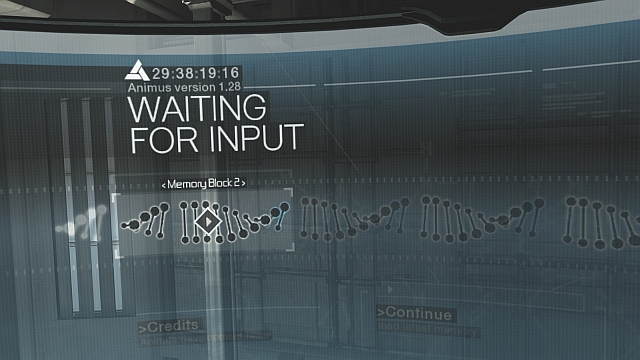

Furthermore, the Animus turns out to be the reason for nearly anything we come across, also – or should I say especially – when it comes to explaining the game’s various shortcomings and limitations. Perhaps you may recall the strange fact that Altair could not swim and any attempts at teaching him (in one of the game’s many bodies of water) resulted in instantaneous desynchronization. The explanation was simple yet clever – the Animus version used in Assassin’s Creed (build 1.28) lacked the appropriate function; it was introduced later, in the version 2.0 (Assassin’s Creed II). The same applies to the subtitles displayed by the game. You may say it sounds like cheap excuses, but isn’t the fact of having such excuses in the first place essential to building the feeling of immersion, as it perfectly fits into the implemented plot and gameplay arrangement the designers decided upon when creating the franchise?

One more thing that should be mentioned is the interface, as it plays a big part in producing that specific historically-futuristic atmosphere as well as immersion. It may sound like a paradox, for we are used to think that an interface would rather stand in the way of immersion than augment it – it’s easier to enter the role when we’re not distracted by numerous windows, bars, and markers. On the contrary, in Assassin’s Creed, given we acknowledge the convention adopted by Ubisoft, all those interface elements seem to be in place as an essential part to the simulation generated by the Animus. Thus, even the use of historically inaccurate terms, like “GPS” when speaking of the in-game map and radar, hardly strikes as inappropriate. One more element of remarkable importance when it comes to sinking into the virtual reality are the menu screens, especially those we see when controlling Desmond - shifting to first-person perspective as we lay down in the Animus and freely move our head to choose the memory sequence (mission) from a glass display spreading before our eyes makes quite the impression even now. It would be a good moment to mention here the procedure, time-consuming and somewhat irritating, we have to go through to close the game – first we leave the Animus, then we exit to the main menu, and from there, finally, to the desktop – although you have to admit that it does serve to support the game’s design idea.

Nothing is true, everything is permitted (and it nets you profit)

When it became obvious that Assassin’s Creed had the potential to became a golden goose, Ubisoft decided on the single plausible course of action – they created a sequel. During development, the creators remained mindful of the voices of criticism concerning repetitiveness and built the sequel upon large amounts of content - we got scores of additional challenges and items to collect, the protagonist, Ezio, got numerous new qualities and options that Altair did not possess (including stronghold management, simple economy, gear upgrades), and the story missions, now in compliance with open-world architecture, were significantly diversified and devoid of the artificial demarcation between investigation and action. To put it briefly, Assassin’s Creed II became a full-fledged sandbox game – and, considering the fact that it is the entry held in highest regard by many, the developers made the right call. However, “right” doesn’t mean it went by without sacrifices – the subtle fun with the Animus itself was over. Events taking place in the present lost their dominant place in the plot to let the players taste the action without delays (off went our strolls from the bedroom to the Animus bed before each new sequence), the synchronization meter was replaced by a “normal” health bar, replenished with medications and extended with progressively better pieces of gear bought from shops; finally, the interface had lost many elements that reminded us that we are taking part in a simulation.

The reason for that was the fact that several new gameplay mechanics extended beyond the premises of the previous title. In AC I the open world was nothing more than background decoration for what was, in essence, a linear, stealth-focused action game; the sequel, on the other hand – as well as later installments – was built upon the idea of offering the player as much freedom as possible. Yes, the mechanics of distracting the guards or blending in with the crowd were present and refined in comparison to the original, and there was still place for missions that required the player to remain completely undetected. Regardless, Ezio was given the abilities such as wielding two-handed axes or using firearms, which hardly comply with the Creed’s second tenant. Furthermore, faster auto regeneration of health/synchronization while operating in stealth had to take a hike as well. Side activities and collectibles had lost their, already scant, plot justification. Admittedly, the game manual for Assassin’s Creed II mentions the fact that things like rooftop races or beating up unfaithful husbands were memories known to have taken place at some unspecified point in Ezio’s history, albeit they were of secondary importance – not very convincing, is it?

You may wonder what does collecting flags scattered throughout virtual reality have to do with reenacting a “historical” figure. I agree, it does sound rather stupid, but in the game manual… there’s an explanation – the flags are an artificial creation, added to the simulation by a worker of Abstergo (Lucy), to hint some less obvious places visited by Altair to Desmond and help him synchronize. In fact, even the piles of hay and carts with various cushioning materials are revealed to be the result of external input to the simulation.

Still, AC II took the whole synchronization business rather seriously and underlined the importance of the present, noting on numerous occasions that Ezio’s adventures in Renaissance Italy are nothing more that means to achieve a specific objective set before the characters living in modern times (visible exceptionally well as the game did a wonderful job joining both narratives in the finale). Alas, with each subsequent installment the initial premise was getting more and more blurred. Especially after Desmond’s story was over – beginning with Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag and onwards the series’ point of gravity was steadily shifting towards events taking place in the past. Each game takes us back to the present for some brief moments to remind the players that “it’s just a simulation” and accustom them with some anachronous gameplay mechanics. It’s been a long time since synchronization was the guideline of what was permitted and what was forbidden – the Animus became a gateway through which more and more bizarre curiosities could be introduced, making sure the franchise remains somewhat crisp with each new installment (vide the Helix Rifts in Assassin’s Creed: Unity)

Although the basic premise introduced at the franchise’s origins is being constantly diluted, from time to time Ubisoft uses the Animus as the explanation for the absence of some things from the game. When it was pointed out that characters in the English version of Assassin’s Creed: Unity lack the French accent (although the whole story takes place in Paris during the French Revolution), the developers blamed it on the machine and its automatic translation algorithm.

While Ubisoft swears that they treat the events used as the pretext for creating various historical reconstructions with due respect, and even have the script prepared for many entries in advance, including some kind of unspecified ending, it’s easy to doubt their credibility seeing how shallow the plot of Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate turned out to be. I bet the developers have got several ways up their sleeve to conclude all the unresolved plot threads, should, for some reason, a need arise to stem the tide of this gold bearing river (not likely, at least not in the near future), but it is very doubtful if another big story arc taking place in the present, like Desmond’s, can be expected. After all, it is not the plot that has spawned the game tens of millions of fans; it was the charm of vivid open-word settings that carefully reproduced actual history and actual places. Currently, however, Ubisoft is rapidly sliding down the sandbox pit trap – while pushing the action dozens of years forward with each subsequent installment, they are getting closer and closer to the rather crowded settings of the XX century, an age heavily exploited by franchises like Grand Theft Auto or Mafia. Even the Victorian Era, the setting of Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate, is separated from them by a scarce 60 year period, resulting in several comparisons between the latest AC and GTA, mainly thanks to the presence of interactive carriages on the streets of London. How will the French deal with this pitfall? Will they stay on course, simply choosing modern settings more distinctive than the ones used by competition? Or will they back-pedal and suddenly decide to jump into the nearly untouched antiquity? That, however, is a matter for a separate article.

The best or the worst?

In conclusion, it is clear that the original Assassin’s Creed is significantly different from later installments. One has to admit that most of the changes introduced by its successors were for the better – the sequels are good, very entertaining games that have to be applauded for their careful historical reconstructions. With each subsequent entry, however, the series’ unique character becomes more and more uninspired, one could even say mundane. If I were to describe with a single word my attitude towards the original AC, I’d say “respect”. I respect its consecutive and uncompromising fusion of plot and gameplay mechanics (the idea of synchronization through the Animus, broadly covered in this article), I am impressed by its detailed reconstruction of the Middle Ages in this intriguing - and troublesome because of the lack of available historical accounts - timeframe of The Third Crusade. And I will remember the unique aura of mystery surrounding the game’s plot. Not to forget about the gameplay itself, as the first Assassin’s Creed was visibly more difficult and demanding than later installments.

After having taken all of the above into account, calling AC I THE best Assassin’s Creed game is not as ridiculous as it may have seen in the beginning. Truth be told, everything depends, as usual, on the taste. If you’re a fan of sandbox, you are unlikely to love the first game. As are the fans of action or even playability in general (still, in its time the parkour Medieval city exploration was a madly entertaining thing for everyone). Assassin’s Creed will win the affection of those who treasure things like atmosphere, immersion, or originality. I suppose not many of you will share my point of view, but – to be honest – I wouldn’t feel bad if the game was never developed into a long and expanded franchise and was rather left to become what it should be remembered as – a one of a kind gem in the history of digital entertainment.